Social Design Manifesto

Ethical Service Design Practice

Exploring the importance of a design code of conduct in social innovation.

Duration

Mar. 2024 - Apr. 2024

Achievements

Research & strategy, illustration & visual design

Collaborators

Royal College of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Centre for Complexity, London Business School

The problem:

One significant issue in the field of design is the absence of a formal manifesto or code of ethics akin to those in professions like medicine, engineering and law. Design impacts every part of our life however designers are not universally bound by a set of ethical guidelines, which can lead to practices that may not always prioritise people’s well-being.

Recognising this gap, we believe that a code of ethics is imperative when designing for communities to ensure our work supports and respects the people it serves.

What we did:

As a team of 13 Service Designers, we co-created a social design code of ethics, outlining principles of transparency, inclusivity, and social responsibility. This code guides our projects, ensuring that our designs are ethically sound and genuinely beneficial to the communities we engage with.

Methodology:

We formed a discussion group to explore what we have learned about our practice and identities while at the RCA. We compiled a list of shared values that we believe summarise what it means to be an ethical service designer. These values shape our approach to problem-solving and our interactions with the world around us, thus influencing our professional roles and sense of purpose.

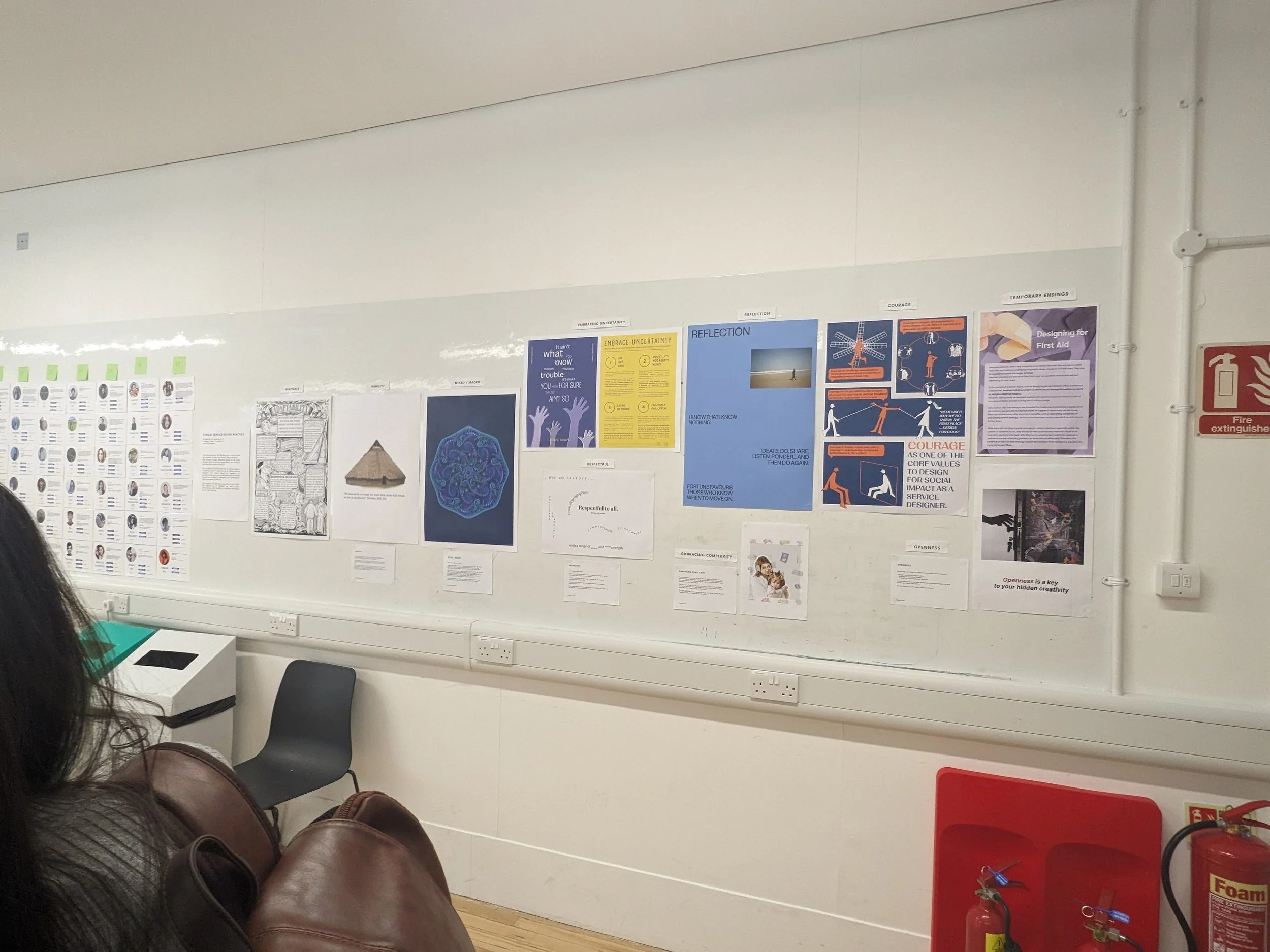

The creation of artefacts in response to each value has allowed us to highlight our unique perspectives while building a collective anthology as our final response. We presented these findings in an exhibition at the Royal College of Art, each taking one principle and making a unique poster around this to exhibit.

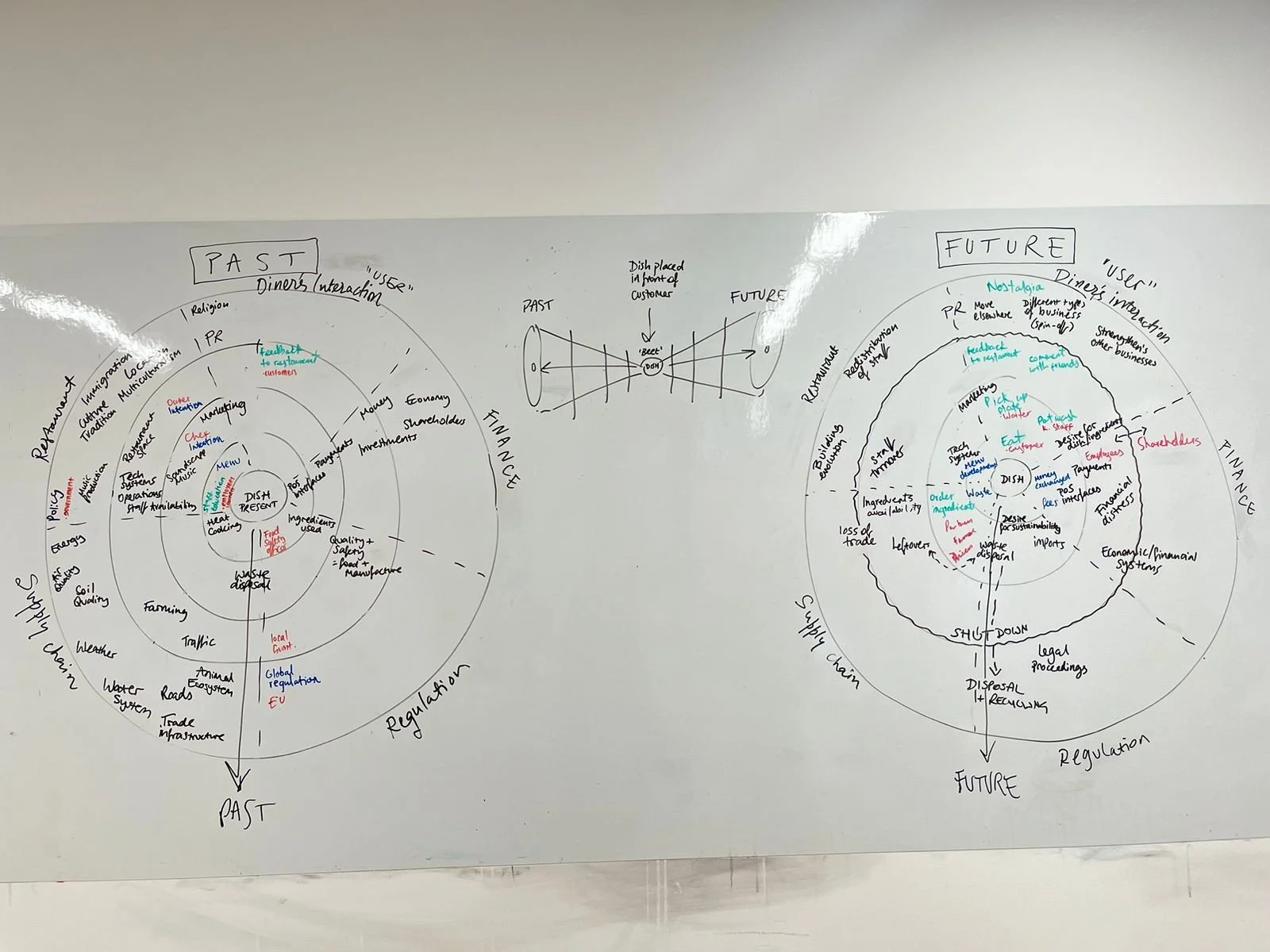

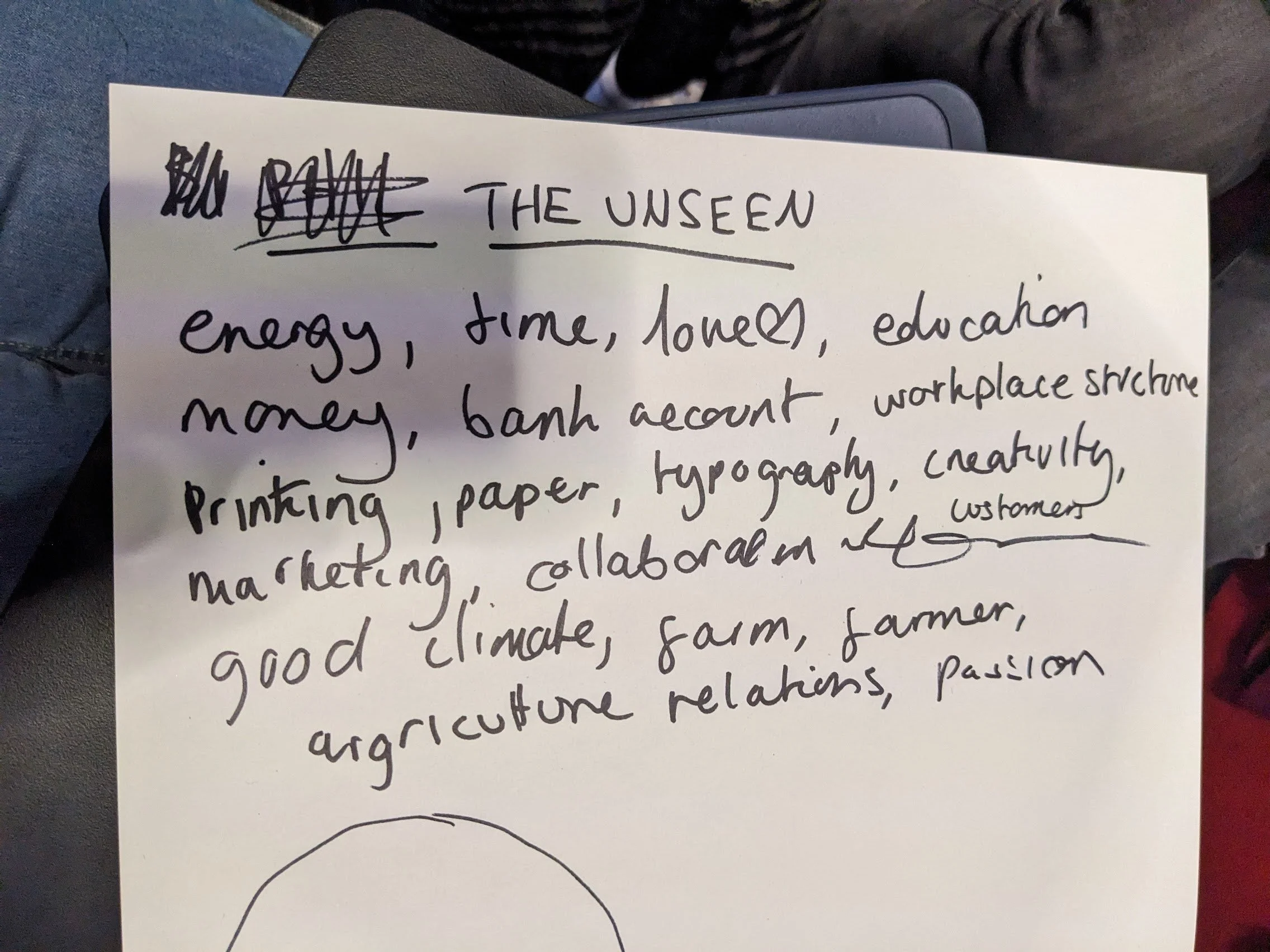

Group ideation sessions:

Systems thinking exercises in collaboration with The RCA, LBS, RISD & the Centre for Complexity

Our final manifesto principles

Adaptability:

With increasingly rapid changes across social, political, moral, economic, technological and climate landscapes, it is imperative for designers to integrate this dynamism into our designs for new services or adaptions of existing ones.

Humility:

The Amazonian indigenous maloca (indigenous longhouse) can house several dozen people under a single roof. Humility here is a core principle in how communal living enables a relational world, where we recognise our agency only as part of a whole.

The mere act of being is at the same time an act of world-making. As a person, I build a world through my interactions and, as designers, the intentional world-making discipline is an output of the world we build inside of ourselves.

Micro/macro:

Micro = tiny | Macro = huge

Playing with scale is inherent in Service Design practice. We look at layered problems in parallel, moving between huge, dancing landscapes and tiny details such as a single human touchpoint. This constant zooming in and out is key to systems thinking, and this skill is especially useful when designing for social impact. Interactions between humans, non-humans and environments are incredibly complex, so working across micro details and macro overviews helps us to be effective service designers.

Embracing uncertainty:

Sitting in the unknown is inherent to service design practice and is a central tenet of both good social design and innovation. As service designers, we value being courageous enough to get lost en route, accepting that not all those who wander (or wonder) are lost.

Additionally, we recognise that to embrace uncertainty (which isn’t always comfortable) we need to:

Spend time re-framing failure as a learning opportunity

Avoid decision paralysis through an experiment-driven, ‘learn by doing’ inspired approach

Encourage continual epistemic humility and ‘strategic’ scepticism to increase rigour in our insights and inspiration.

Embracing complexity:

Embracing complexity is a central theme reflected in my previous service design work. My project focused on capturing the intricate journey of a young mother navigating her new identity and relationship with her baby in the first three years of motherhood. My project “Leisure for Mums” conducted in Hounslow, revealed the complex realities of young mothers. This example demonstrates how embracing complexity allows us to design solutions that are deeply empathetic and responsive to the nuanced experiences of those we seek to support.

Courage:

In the realm of societal design, courage becomes one of the core values for design for society. First, courage to challenge assumptions, confront complexity, embrace risks, and address unfamiliar issues.

As we prioritise users in our design process, we often find ourselves swaying amidst stakeholder interests—a dynamic not necessarily negative, yet it's crucial to remain grounded in our initial purpose as designers: to design for good, not for one of the stakeholders that has power. It's also about the courage to communicate all user needs, not the idealised version based on stakeholder preferences.

Lastly, courage lets us iterate and reflect persistently, even when it entails acknowledging flaws or encountering setbacks along the way.

Respectful:

Isn’t respect fairly basic? But it is surprising how often it can be lacking in society as well as the impact that its presence can create. A critical value that design brings is respect for all, without conditions and judgements.

Openness:

Becoming more open to others encompasses various aspects:

Being receptive to others' ideas

Utilising the talents of others

Sharing unconventional thoughts

Do you want to expand your abilities as a designer? Open up and share your ideas with others. It's the shortcut to find your hidden creativity.

Reflection:

To understand is the marriage of what you comprehend and what you know. So knowing that you know nothing is liberating.

It’s also the cornerstone of my practice. You don’t need to start with reflection, but reflecting enables you to take a step back, see the bigger picture and begin to embody these shared values for what we believe a Service Designer should be.

Reflection facilitates illuminated beginnings, which begs illuminated endings. Knowing when to move on is a big part of that journey.

Temporary endings:

As designers, we often make and design solutions without considering if, when & how it should be discontinued. In the context of systemic issues, addressing the root cause usually is a slow process and band-aid solutions might be necessary in addition, to managing immediate concerns or mitigating negative impacts.

Using the metaphor of ripping off a band-aid is a reminder that band-aids offer short-term benefits alleviating symptoms, but do not address the underlying problems.

Balance:

Pursuing the delicate equilibrium found within contrasts, the piece strives to recognise the interplay between opposing forces.

Challenges often demand the discovery of a healthy equilibrium between opposites, enabling the essence of both to be embraced without leaning towards extremes.

Recognising the inherent biases present in human nature, individuals seek to understand and embrace them, thus making it essential to find balance in both their lives and work.

Contributers

Melis Ozoner (LBS), Juliana Rojas Reyes, Bashiru Lawal-Shardow, Tanaya Bhalve, Ruby Hardy Bullen, Elena Seo, Dewi Rachmandari, Rasi Surana, Venkat Rao, Ben Broad

Guides

Judah Armani (RCA), Harris Elliott (RCA), Toban Shadlyn (RISD, Centre for Complexity), Justin W. Cook (RISD, Centre for Complexity)

My poster & contribution

Presenting our findings to Utrecht University of the Arts

Going forward:

These principles will guide my practice during my career as a designer.